The best thing, though, in that museum was that everything always stayed right where it was. Nobody’d move…Nobody’d be different. The only thing that would be different would be you…I kept thinking about old Phoebe going to that museum on Saturdays the way I used to. I thought how she’d see the same stuff I used to see, and how she’d be different every time she saw it.

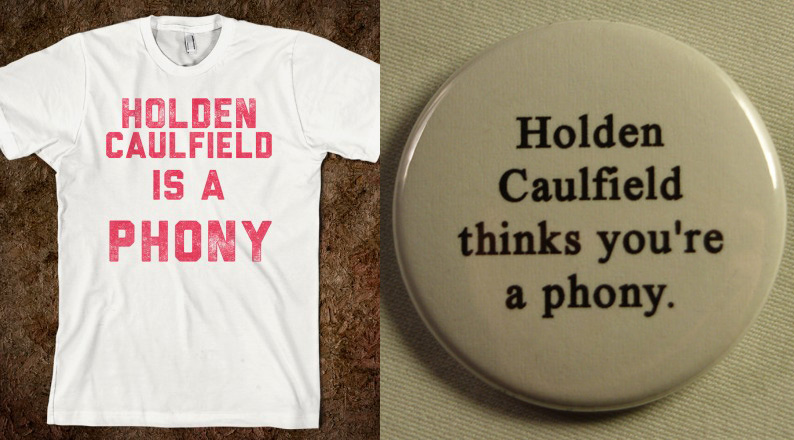

The Catcher in the Rye is an interestingly divisive book; there are people out there who mark it as life-changing and then there’s those who really, truly hate it. “Holden Caulfield is a phony” seems to pop up as much as “Holden Caulfield thinks you’re a phony.” The Catcher in the Rye is the story of the teenaged Holden Caulfield getting kicked out of his prep school—actually, getting kicked out of his fourth prep school—and hanging around New York city for a couple days, hating everyone or else feeling bad for them. He loves his little sister and seems to merely tolerate the rest of the world. Over the course of his brief break from reality he gradually reveals details of his life through the first-person narrative.

You don’t have to relate to someone, or even have to like them much, to empathize with them. It isn’t Holden Caulfield’s perceived or accepted relatability that makes The Catcher in the Rye a classic of young adult literature; it’s the fact that Holden is a complete and fully-formed character. Holden may be a mess of conflicts and contradictions, but it makes him real. In fact, people who dislike The Catcher in the Rye tend to react not to the book itself, but to the character of Holden. In people’s negative reviews of The Catcher in the Rye Holden Caulfield’s a “slacker,” a “self-absorbed whiner,” “incredibly stupid,” the “biggest phony he knows,” someone who gives some readers the urge to “take [him] by the collar and shake him really, really hard and shout at him to grow up.”

They hate his whining, they think his cynicism is unforgivably self-indulgent, they think he has no excuse to be the way he is: but it’s not that he’s badly-written fictional character, he’s just some guy they hate. He may have become an icon or an archetype outside the book, but within The Catcher in the Rye he’s just some kid.

The Catcher in the Rye is the grandaddy of young adult literature because Salinger wrote about the rich internal life of a teenager—not necessarily a gratifying or self-assured internal life, but a real consciousness and thought process: a new phenomenon in its time. Teenagers were around in fiction, but generally on the periphery of adult’s lives or in a sort of Hardy Boys capacity—convenient characters for children’s stories because they had a little more autonomy and were less likely to give off a ‘child endangerment’ vibe during action-heavy adventures. Salinger gives Holden Caulfield a voice that is distinctly his own; it may resonate, it may irritate, but no matter how you cut it, it’s all his.

Maybe the readers who are completely put off by Holden’s continual, and generally hypocritical, scathing indictments of phonies had no trouble transitioning from the inner-life of a child to that of an adult, or maybe they’ve forgotten it. Well, I’m glad for them, but for many others the disillusionment can be painful—this isn’t the ‘what do you mean Santa isn’t real?’ disillusionment, it’s encountering how petty, mean, and uncaring the world can be. Realizing the terrifying size of it, the realities of loss, the whole general existential crisis of it all. It can be difficult and overwhelming, and people haven’t always built up the necessary defenses; the ability to recognize kindness, the friends, the things that make the world worth the little sadnesses. It shouldn’t be surprising that many people will identify with Holden, particularly those in that liminal space between childhood and adulthood. I wasn’t an unhappy teenager; I have very fond memories of high school and my time there, but I find my hackles rising when people use ‘teen angst’ as a dismissive and patronizing term, as if a person’s feelings aren’t fully legitimized until adulthood.

All that said, although The Catcher in the Rye shouldn’t be written off because of dislike for the protagonist, it isn’t necessarily a book that will work for everyone. Some people won’t be engaged by the lack of recognizable plot—no steady build to conflict and resolution here, this is a classic ‘slice of life’ piece that is essentially a character study. It can be slow going, and the repetitiousness of Holden’s choice phrases can compound the effect. What saves the pace is the chance to piece together Holden’s character from his gradual reveal of details about his life that led him to this point, small reveals which keep the reader from losing interest in the fairly unremarkable events—Holden wiles away time in New York and thinks about doing things that he’ll probably never get around to doing.

As for a personal reading, well, I certainly don’t relate to Holden—I read it in high school and I had a fuzzy memory of disliking Holden but enjoying the book; I find now that he shows an almost comical lack of self-awareness of his many little hypocrisies and most generalizations he makes are idiotic or insulting, but it’s recognizable that he’s “riding for some kind of terrible, terrible fall” and he’s already way out of his emotional depth. You can see the boy Holden used to be; the boy who played checkers with Jane Gallager and moved seats in the theatre so he and his brother could sit closer to the guy who played the kettle drums because they liked him best: “He only gets a chance to bang them a couple of times during a whole piece, but he never looks bored when he isn’t doing it. Then when he does bang them, he does it so nice and sweet, with this nervous expression on his face.” Holden was yanked out of childhood innocence in some fairly brutal ways; the death of a beloved younger brother from leukemia; the corpse of a bullied classmate who jumped to his death, still dressed in a sweater Holden had lent him—“his teeth, and blood, were all over place.” Holden’s zealous cynicism doesn’t bother me because I read it as a defense mechanism, something that was easy to swallow because he was so clearly lost; a teenage boy talking aloud to his dead brother.

The most engaging aspect of an unreliable narrator is the access to their own internal narrative; the dissonance between thoughts and actions or perceptions and reality. For all that Holden waxes like a misanthrope, he isn’t needless cruel in his life, to all those people he seems to alternate between hating and pitying; all his loathing is turned inwards. How could I resent the boy who, when he speaks with confidants about incidents that have distressed him, reveals that his real distaste is reserved for petty cruelties?—the secret fraternity at his prep school that excludes a boy “just because he was boring and pimply,” or the Oral Expression class in which students are encouraged to heckle speakers who fail to keep on topic, where a nervous boy telling a family story is shamed. The boy who wants to be the catcher in the rye—who dreams of standing guard over happy children at play.